|

|

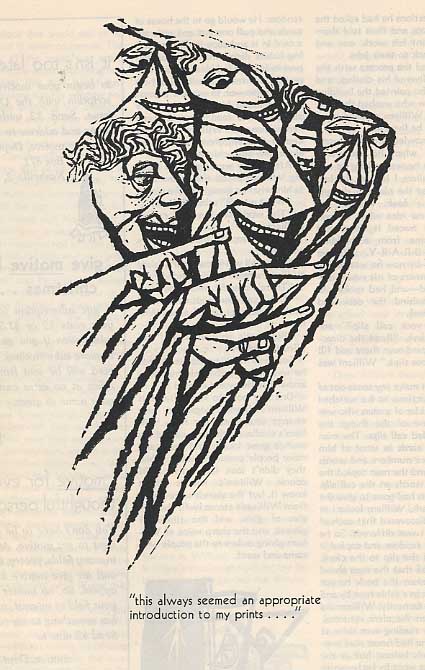

R.O. Hodgell Introduction

Robert O. Hodgell

APPRECIATION

My father, Robert O. Hodgell, was a remarkable man and a consummate artist. His output over a sixty year career was staggering.

Even forty years ago, a visiting journalist wondered if " he didn't have all Seven Dwarfs hidden away, working compulsively creating sculptures, paintings, and prints like mad." She reported "unbelievably high piles of cut-out linoleum bits by his print block," a fireplace; "filled with chunky little angels," portraits of "real and not real but too real people, gigantic paintings of cars and houses and animals and churches," prints drying on clothes lines, on the floor, on beds. "He's through," she added, "with his tragic angel period, his turtle period, and is in an interesting one which produces corset-like castles with the protruding heads (mostly noses) of soldiers sticking out" (Caffery).

I also remember a rubber chicken hanging from a light fixture and a reproduction of his controversial "Head of Christ" framed with a note from some worthy church lady declaring that it wasn't her idea of Jesus -- his first fan letter, he told me, with a wry smile somewhere in that bushy red beard of his.

I also remember a rubber chicken hanging from a light fixture and a reproduction of his controversial "Head of Christ" framed with a note from some worthy church lady declaring that it wasn't her idea of Jesus -- his first fan letter, he told me, with a wry smile somewhere in that bushy red beard of his.

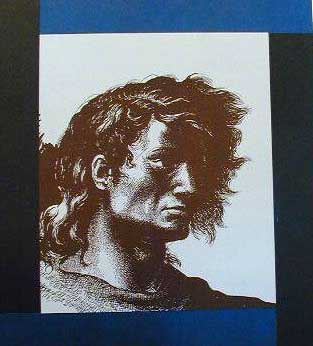

(Yes, this was once a startling way to portray Jesus. All his life, Dad had a running feud with what he called the "bearded lady" versions.)

Thirty-one years later following his death from colon cancer, I found myself in possession of a similar house crammed to the rafters with my father's work, surrounded (among other things) by his innumerable often uncomfortable self-portraits. They too seemed to ruefully smile at me: see what a mess I've landed you in. Sorry.

Two-thirds of his art I donated to Eckerd College where he taught for fifteen years. Some I gave or sold to his friends. Two U-Hauls' worth came home with me. I'm still sorting them out. Beyond that, you can find it in many homes, churches, and such permanent collections as

--Library of Congress

--Metropolitan Museum of Art

--Des Moines Art Center

--Joslyn Art Museum

--University of Wisconsin

--Kansas State University

--Bergstrom Museum

--Ringling Museum of Art

--St. Petersburg Museum of Fine Arts ("A Legacy: Robert Hodgell")

Therefore, what you find represented here is only a sample of his prodigious creativity. His friend and fellow artist Jim Crane said in an eulogy that Dad's fame rested in the hands of the writers, by which I assume he meant art historians (Crane). I am only a novelist, and Dad was primarily visual, with a deep mistrust of mere words, words, words. The best I can do is give you some context, then let his images speak for themselves. Their wit and wisdom remain far more eloquent than I could ever be in their behalf.

Caffery, Betha. "Wife Solves an Arty Problem," St. Petersburg Independent 2/14/69 1-B.

Crane, James. "The Art of Bob Hodgell." Gallery Talk for the Academy of Senior Professionals. Eckerd College. 12 April 2001.

"Legacy: Robert Hodgell" April 2009 Eckerd College

http://www.eckerd.edu/registrar/hodgell.php

BIOGRAPHY

Robert O. Hodgell was born in Mankato, Kansas, in 1922. His parents were schoolteachers, then his father turned school administrator and was ordained a Methodist minister. He actually died of a stroke suffered in mid-sermon, caught as he fell by his elder son Murlin (Hodgell, Murlin). Bob enrolled in children's art classes at Washburn College. In high school his interests switched to track where he was nicknamed the "Kansas Kangaroo" for his high jumping style. He also threw the javelin 165 feet, ran the 100 yard high hurdles, and captained the basketball team ("Awards Winner").

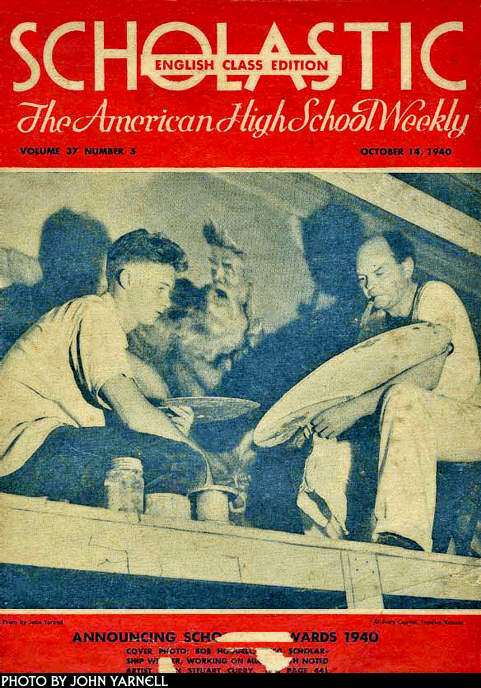

In 1939, he stopped by the Topeka State House to watch the celebrated artist John Steuart Curry work on its murals. Curry hired him, first as an apprentice and later as his assistant. That summer, in addition to cleaning brushes and palettes, Bob finished details on tornadoes, buffalo, and even the central figure of John Brown. Scholastic reports that "there are some flowers and herds on which Bob did a large proportion of the work" ("Awards Winner").

In 1939, he stopped by the Topeka State House to watch the celebrated artist John Steuart Curry work on its murals. Curry hired him, first as an apprentice and later as his assistant. That summer, in addition to cleaning brushes and palettes, Bob finished details on tornadoes, buffalo, and even the central figure of John Brown. Scholastic reports that "there are some flowers and herds on which Bob did a large proportion of the work" ("Awards Winner").

At the time, Curry was one of the most famous artists in the country. He belonged to the Regionalist school now best known for Grant Wood's iconic "American Gothic." Curry was the first artist in residence at an American university (UWM), a distinction that put him on the cover of Life magazine. (Strange but true: he was sponsored not by the art or even the humanities department but by agriculture.) To become his apprentice, therefore, was a huge honor for young Bob and he worked with the artist for the remaining six years of Curry's life, with time out for World War II.

"Curry was the biggest influence in my life," Bob told reporter Joan Altabe in 1991. "I learned on the job. I think starting out in the apprentice system rather than the educational system makes a difference in your outlook. You see art as a calling instead of as a profession" (Altabe).

Of course, the war disrupted a vast number of lives, and Bob's was one of them. As a navy trainee, he attended Dartmouth and Columbia Midshipman's School, graduating to become the skipper of a LCT in the Gilberts and then a LSM engineering officer in the Philippines. During this period he first grew his signature beard so as to distinguish himself from the rest of his teenaged crew.

To give his own summary of the next fourteen years as narrated to Margaret Rigg for motive magazine, "Back to Wisconsin, Curry, track. Wesley (student). Got married [to Lois, my mother] and a Master's degree, freelanced as an artist for a year. Went to Des Moines Art Center as instructor and resident artist, three years. Divorced, and went to Mexico to paint and study. University of Illinois graduate school-teaching and chief illustrator for "Our Wonderful World" encyclopedias for three years. Then, more freelancing art at Urbana, Illinois. Married and widowed. Became art director, University of Wisconsin at Madison for their Editorial and Communications Services, Extension division. Have illustrated four children's books (working on a fifth), illustrated articles and stories in Playboy and other magazines, have been exhibiting prints and paintings for almost twenty-five years now, had over twenty one-man shows" (Hodgell, Robert).

In 1962 he moved to Florida to take up a teaching position at Florida Presbyterian College with the two conditions that he neither shave his beard nor give up his association with Playboy. In 1972, FPC became Eckerd College. Bob married again and continued to teach until 1977 before quitting to resume art full time.

From 1977 to 2000, his rampant creativity led him into all manner of media, resulting in many more art shows and innumerable awards. "His impact on the art community is immeasurable," says Arthur Skinner, professor of visual arts at Eckerd and a former colleague. "He was a true artist if ever I have known one, one for whom art was his life, one who worked tirelessly, virtually every day of his life" (Basse).

While his subject matter was as varied as the medium in which he expressed it, he is best remembered for his religious themes. According to B. J. Stiles, editor of motive, his "woodcuts and linoprints brought new insights and fresh vision to several generations of people of faith, reared in the comforting confines of Sallman's Head of Christ [one of the afore-mentioned "bearded ladies"] and countless bad reproductions of Durer and Rembrandt. Hodgell illuminated truths and insights from both the Old and New Testament that had long been dulled and obscured by well intended but nonetheless trite teachings and insipid preaching. His work was tacked to bulletin boards in dorm rooms and campus religious centers on several continents. His work endures -- and inspires" ("Century Marks").

While his subject matter was as varied as the medium in which he expressed it, he is best remembered for his religious themes. According to B. J. Stiles, editor of motive, his "woodcuts and linoprints brought new insights and fresh vision to several generations of people of faith, reared in the comforting confines of Sallman's Head of Christ [one of the afore-mentioned "bearded ladies"] and countless bad reproductions of Durer and Rembrandt. Hodgell illuminated truths and insights from both the Old and New Testament that had long been dulled and obscured by well intended but nonetheless trite teachings and insipid preaching. His work was tacked to bulletin boards in dorm rooms and campus religious centers on several continents. His work endures -- and inspires" ("Century Marks").

Altabe, Joan. "Robert Hodgell Didn't Fit Typical Image of Artist." Herald-Tribune 3/7/00 6B.

"Awards Winner Gets Job with John Steuart Curry." Scholastic 14 October 1940, 44.

Basse, Craig. "Artist and teacher Hodgell dies at 77." St. Petersburg Times, 3/5/00 3B.

"Century Marks." Christian Century 22-29 March 2000, 327.

Hodgell, Murlin. Personal Interview. 3 March 2000.

Hodgell, Robert. "Artist: Robert Hodgell." Margaret Rigg, compiler. motive Nov 1959, 15.

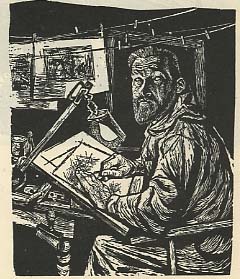

THE PRINTS: HOW DID HE MAKE THEM?

"I generally start with undetailed thumbnail sketches, trying to find the most effective over-all image and form of organization. Then I do full-size rough pencil sketches on tracing paper, making corrections on overlays. This may be one sitting or many days of reworking until the image seems right."

"Next I ink the pencil sketch with a brush and try to approximate the weight and mass of the final print; trace the sketch on the block (chalk on back of the tissue); and re-ink the drawing on the linoleum, this being a final version of the drawing rather than a tracing. I use only one tool for cutting, a shallow gouge, and battleship linoleum (with no wood backing). The cutting process is guided, but not controlled, by the inked areas on the linoleum. I like to use the gouge like a brush, "painting" as I go, letting the feel of the tool decide the actual cutting. If a major revision seems advisable, I make the correction in chalk and re-ink. The area being inked and proofed, partly to avoid over-cutting and partly for the visual advantage of a darker surface against the lighter cut area which more nearly approximates the contrast of the print."

"Next I ink the pencil sketch with a brush and try to approximate the weight and mass of the final print; trace the sketch on the block (chalk on back of the tissue); and re-ink the drawing on the linoleum, this being a final version of the drawing rather than a tracing. I use only one tool for cutting, a shallow gouge, and battleship linoleum (with no wood backing). The cutting process is guided, but not controlled, by the inked areas on the linoleum. I like to use the gouge like a brush, "painting" as I go, letting the feel of the tool decide the actual cutting. If a major revision seems advisable, I make the correction in chalk and re-ink. The area being inked and proofed, partly to avoid over-cutting and partly for the visual advantage of a darker surface against the lighter cut area which more nearly approximates the contrast of the print."

"Color blocks are cut in the same manner. A print of the master block is transferred to another piece of linoleum and worked directly. I seldom work out the color patterns on paper and seldom have more than a vague idea what the color scheme will actually be. This comes from experiments in pulling proofs."

"Printing is all by hand. The block is inked, paper laid on it, pressed to the block with a rubber roller, and rubbed with fingernails and hand until the paper is judged to be printed by the feel of the relief on the back."

Quoted by Norman Kent in "Religious Relief Prints," American Artist, April 1961, 38 ff.

On Painting Nudes (from Notebook #1)

"As to painting naked ladies, any character who joins a drawing class with his glands all aglow quickly discovers that [he is] too busy and frustrated with the sheer mechanics of trying to record the human figure with its infinite variety of muscular tensions and changes in shape, linear rhythm and volume which the slightest movement brings about. He discovers the girl on the beach is infinitely more mysterious and sexy than the unadorned nakedness he tried to analyze and record in the classroom."

Price list:

Most of these pieces are in my possession (except for those with asterisks in their titles) and are for sale. Ask for specifics.

Music: Seeger, Pete. "My Father's Mansions." The Essential Pete Seeger. CD. Vanguard, 1986.