|

|

Strange Wisconsin

Strange Wisconsin: More Badger State Weirdness. Ed. Linda S. Godfrey.

Madison, WI: Trails Books, 2007. Pp. 110-1.

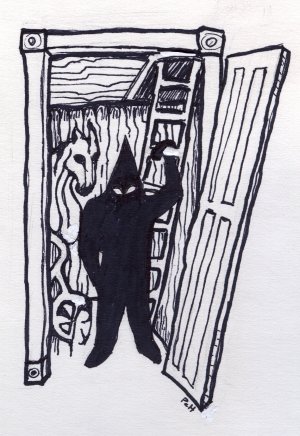

The Gnome King

By P. C. Hodgell

It was the late summer or early fall of 1959.

I was standing in Mrs. L's untamed backyard, wishing there was someone to play with. All our neighbors were my grandmother's age or older, like Mrs. L with her gummy, pink-rimmed eyes and squat body stuck together like a jackdaw's nest, who sometimes babysat me when Grandma had to go out.

I don't know where my parents were. Divorced. Gone.

I didn't know it then, but Mrs. L spent her nights sitting on a chair on her darkened, second floor landing, staring down into our living room through our bay window as if onto a lit stage.

There, she had watched my mother and three uncles grow up.

Perhaps she had been watching the day that my grandfather quietly died on the narrow, sunny bed that Grandma had made for him in the bay.

Perhaps, soon afterward, she heard Grandma scream when the telegram arrived to say that her oldest son, Roger, was dead, shot by his own rifle in a New Guinea army camp thanks to a faulty safety catch.

Congratulations, Mrs. Partridge: You are now a Gold Star Mother.

Sometimes I heard Mrs. L's daughter Babe shriek with delirium tremens in the middle of the night. Our bedroom windows were very close. Did Mrs. L leave her chair to check or did she continue to sit, waiting for the curtain to rise on the life next door?

Some of this came before, some after that summer (or fall) day in 1959, when Eisenhower was president and I was eight. Time ebbs, time flows. Memories swirl on its current like fallen leaves on dark water.

So there I stood, idly gazing across Mrs. L's wild backyard into our scarcely tamer one, and what I saw was our shabby old garage with its door sagging open. Once it had been a barn. As old as the house, built in the late nineteenth century by my grandfather, it had stabled Great Aunt Georgina's horse Birdie. Georgie married a doctor who went west to seek his fortune, only to disappear in the 1907 San Francisco earthquake. Another faulty safety catch, this one tectonic. Another widow, but this time no gold star. Instead, Georgie earned her own M.D., and Birdie took her on her rounds in those long-ago days when doctors still made house calls. I liked to think of Birdie standing in her stall, perhaps swishing her tail at flies, patiently waiting for the slam of the back screen door and the brisk step of the dumpy little woman with the determined jaw and the black bag.

Time flows, time ebbs.

Now the barn was a ruin, full of junk exiled from the house in slow, decaying transit to the city dump. Standing inside, I would have seen the cracked, carven headboard of my grandfather's bed, the skeleton of an uncle's bicycle, a warped quilting frame. Perhaps my grandmother's record player was tucked in some dark corner, but I think not. The thick, Edison disks might still be piled in a closet upstairs, but Mrs. L had borrowed the machine ages ago and never returned it. She had been our babysitter for generations. She had a key. Things disappeared.

Leap ahead twenty years, maybe thirty. Mrs. L and Babe are both dead. We have bought their house and are about to tear it down to enlarge our wild, narrow yard. I am standing on the second floor landing, at dusk on the last day of the year, looking down through our bay window as if onto a lit stage. What if I should see Mrs. L sitting at our dining room table? What if she should look up at me with her red-rimmed eyes and smile her toothless, hungry smile? If there were a chair behind me, might I sit down and watch her watching me watching her? But there is no chair, no Mrs. L, only the detritus of two wasted lives. One room is full of small, unopened boxes showing ties, handkerchiefs, underwear through dingy cellophane windows, light-fingered from many different shops. Another is carpeted with old, family photographs. Who are all of these people? Why did Mrs. L's son abandon them here? He never came by except once to mow her lawn and ours too, without permission, destroying the clump of flowers that the Monarch butterflies loved. If I keep looking, perhaps I will find Grandma's record player, my mother's hand-made Halloween costume, my collection of tiny glass horses, all named Birdie.

Leap back to the sagging barn where a real horse once lived. I am eight, and bored, but even if there were someone to play with, would we have dared each other to enter that moldering ruin? The breath out of its half-hinged door is as rank and earthy as the grave. A ladder leads up to a second floor soft with rot under a leaking roof, unsafe and unwelcoming, but as familiar as the secret recesses of one's own aging body.

As acquisitive of time as of things, Mrs. L lived to be well over one hundred. She had a letter from the President to prove it.

Congratulation, Mrs. Lewellyn: You are still alive.

I am now more than half that old, so why do I remember that day, that moment, so vividly, almost fifty years later?

Because of what I saw. In the barn. By the ladder. Some... thing, darker than the shadows around it. A black, squat silhouette with a pointed head or perhaps a hat, gripping a rung of the ladder with one hand, red eyes staring back at me. What was in that look? Nothing wholesome. Nothing human. Something cynical and knowing. Then, in a blink, it... no, he was gone.

Please understand. At the time I had no idea what I had just seen. Today, I am still not sure. But when I think about it, it seems to dangle at the heart of so many childhood memories, like the husk of a spider in the tatters of its web, trapped between dirty window panes. What is imagination for, if not to make patterns?

"Only connect," wrote E. M Forster.

We can only try.

So.

Gnome king who guards the treasures of decay, the things we can't let go but can no longer bear to touch, was it you I saw that day? If so, I think you usually lived next door with Mrs. L. Did you try on Mr. L's shoes with the socks still in them, just the way he left them the day he died, long before my own birth? Was it you who put fresh seed in the cage of her long dead canary, or filled the room off the kitchen with garbage, or flipped photographs onto a bedroom floor as if discarding one card after another in a long, losing game of solitaire? Good-bye, good-bye, good-bye...

If I had thought to look up, would I have seen your red eyes set in Mrs. L's gnomish, hunched figure on the landing, staring back down at me? If I had seen, today would I be staring out of the ruins of our barn, one hand possessively gripping the rung on a ladder to rot?

Mrs. L's house is long gone, in its place a wide, wild garden where butterflies dance. Sometimes, though, I think I see its lit windows hanging, empty, in the night.

But you visited our barn too, after Birdie died, after decay crept into the corners and its weight made the upper floor sag, before we tore it down. Your red eyes jeered at me that day. Why? Because we cling to useless things while we forget the mundane moments that create the texture of our lives? I hear your unspoken taunt:

Time sinks into itself as if into rank water. One by one, you all sink with it, the fragments of your petty lives gone forever. Therefore, hold on. To anything. To everything.

But that's a trap too, isn't it?

Gnome king, guardian of the threshold between life and the ultimate dissolution into chaos that is death, I will choose what to keep, what to discard, what to value. You taught me that, you and Mrs. L. My mind is no ragged web, heavy with dead flies, no floor sagging under the weight of your useless "treasures." Underground with them, to the junkyard or the grave where they belong. I will follow soon enough; but until then, I will live.

Those are my thoughts now.

Then, as a child standing just outside the barn's shadowed doorway, myself still in the light, I only thought, "This is 1959. This moment is real. Whatever I just saw, I will never forget it."

And I never have.

Audio recording by P.C. Hodgell.